Townsteading

What does it take to make a home on the range?

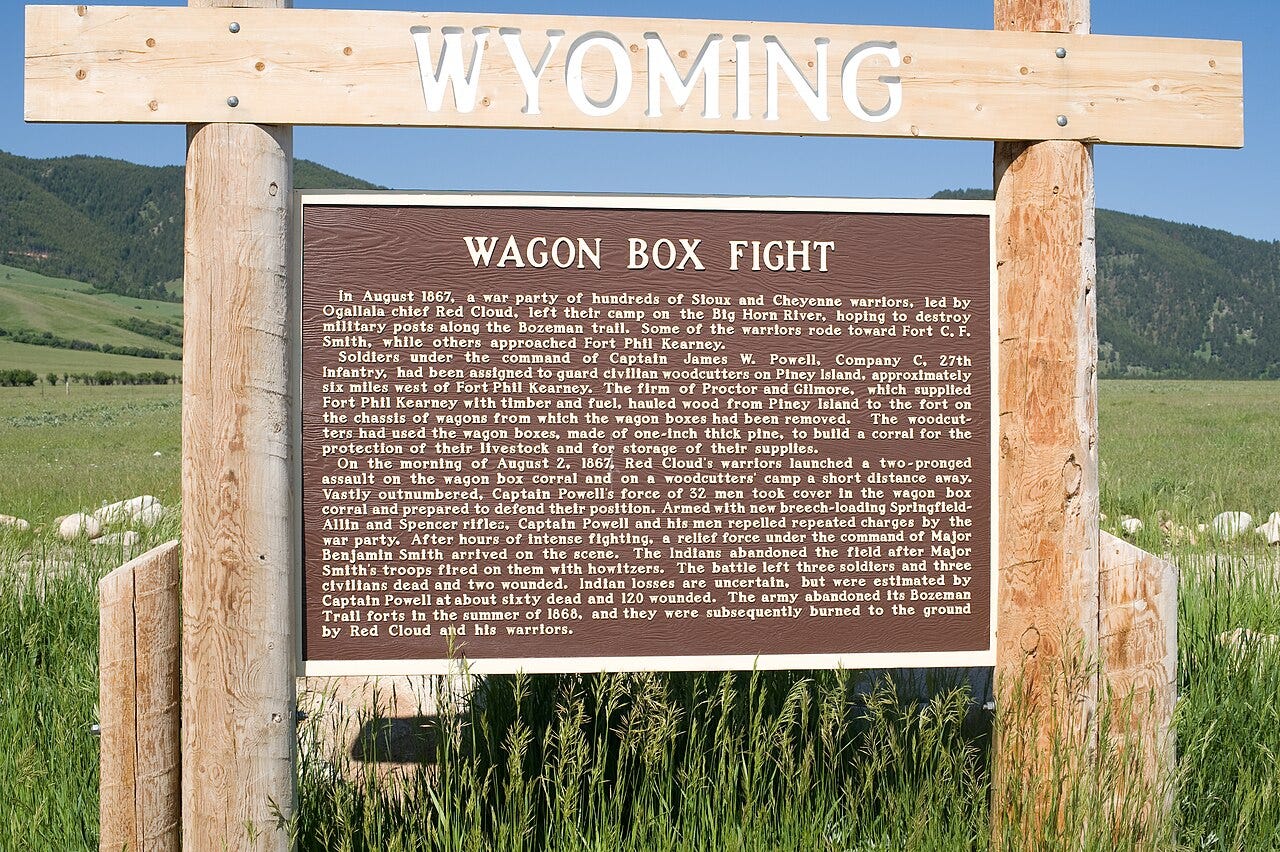

The Wagon Box Inn in Story, Wyoming — named for the 1867 Wagon Box Fight near historic Fort Phil Kearny on the Bozeman Trail — recently sent out a notice for their second annual Homesteading Symposium. The Wagon Box Inn was long a little old knotty-pine hotel, with some RV hookups and a wagon-wheel chandelier-lit restaurant, all camped in an old unincorporated vacation community in the hills south of Sheridan. A few years back it was purchased by some coastal libertarian tech bros seeking rural co-working space, Covid escape, back-to-the-land cosplay, etc. Their takeover was controversial. Per their own website, the Wagon Box Inn now “maintains a loosely Christian mission, encouraging righteousness and the flourishing of the good, the true, and the beautiful—the Kingdom of Heaven."

Coastal types using coastal money to buy up chunks of the Mountain West in a feverish bid for some sense of authenticity has become more than a bit of a trope out here in the formerly wild west. Rocky Mountain property prices have exploded. Most folks born and raised out here can no longer afford to buy homes. The pay rate differential between the mountains and coasts is just too great, outside of Denver or Boise. Locals cannot compete with coastal money. The whole region is being gentrified (colonized?) by folks in love with Yellowstone. Meaning, the comically inaccurate series about life in the Rocky Mountain states, not the first National Park (which does in fact sit just down the road a bit in local terms.)

As a child, I spent quality family time at a log cabin near the Wagon Box Inn, back in the early 70s. I can recall driving by the Inn a dozen or more times, in the back of one of my dad’s succession of station wagons; even eating there a few times. So, when I learned of their first “homesteading” event last year, I wrote and inquired about the program. I imagined a long getaway weekend for Michael and I (he is my husband, if you are new here, and yes we are both male.) We could listen to some interesting speakers, and hopefully have a side visit with some my cousins. They still own their nearby family cabin.

The Wagon Box event organizers seemed affable at first, chatting up their program plans a bit with me via email. It felt like a friendly dialogue, so I shared some of my own story and interests. They stopped responding after I mentioned my husband. Curious, I waited a bit and then wrote again to specifically ask if a gay couple would be welcome at their event.

(Insert crickets.)

So, I figured I had learned something about the newfangled Wagon Box and their notions of “homesteading.” The Venn diagram encircling migrant coastal “homesteaders,” bible-swinging anti-vaxxers, and gun-slinging white nationalists, tends to intersect in a collective disdain for “degenerates,” like us homos who were born to make more culture than babies. The ancient and obviously enduring role of homosexuals in the greater mammalian biological imperative is too indirect for some religious folk to comprehend. Science is hard.

So, I don’t expect to be calling upon the Wagon Box Inn again. Which is too bad. Unlike the East Coast kids who bought the joint, I have authentic, local family history with immigrant homesteading and the Wagon Box locale. I also feel passionate about the kinds of community organizing that often get passed off these days as “homesteading.”

But, it seems homos have no place in these folks’ notions of how to create a “home.” Some children are destined to be kicked out of some people’s families.

The whole notion of homesteading — making a life and building a community for yourself and those you love — pulls my Grandpa Nick into mind. He was a land-grant immigrant from Luxembourg who spoke in a thick “Deutscher” accent and had an old family way with brandymaking. I never met the guy. But, I keep a mental snapshot of him from a photo. He is sitting in the living room of the house I knew for myself as “Aunt Marie’s place,” in Billings. She lived there long after he died. The curtains on his right have a leaf and vine pattern. They are drawn against the sun glowing into the shadows. He is squat, broad, and spread in a big easy chair, smoking a cigar, looking much like my Uncle Paul, his second son. This old black and white photo from the 1940s is from an album I kept when my sisters and I sold our own family home ten blocks away, after our own parents had died. Dad was his third son.

My Grandpa Nick arrived at Ellis Island on the U.S.S. Finland in 1907. He proved up 180 acres of scrubby Homestead Act farm land in Stillwater County, Montana, on October 14, 1913, per some Bureau of Land Management records I recently obtained. He and his wife Katherine, also from a Luxembourgisch immigrant family, raised five children. Children they once posed along the footboard of a black Ford Model T, for another old family photo that serves as a lens into my family’s immigrant history. He sold the farm after three of his four boys came home from the war (the fourth and eldest had stayed home to run the farm, as was allowed by the laws of war in place at the time). The whole post-war family ended up in Billings, living in the house near Pioneer Park where this old photo was taken. The boys each eventually married and left. Aunt Marie tried to marry and failed. She kept the family home. Grandpa Nick died in 1949, 17 years before I was born. Family stories make him out to be a surly old-world character who never fully adapted to life in America. He emigrated to establish a homestead, raise a family, and farm the land. Some kids do not want to stay down on the farm. Some land is drenched in alkali.

My grandfather’s homestead land was bad. On the other hand, the house he bought in town thirty years later was close to jobs. At one point it even served as H.Q. for the cleaning business my dad started with his mom, named Schuman Duracleaners. I own a seventy or so year old ball point pen imprinted with this name. Dad later got out of “duracleaning” and went into the imprinted promotional products business himself.

In recent years, and particularly since Covid, “homesteading” — or some facsimile thereof — has been swinging back into a boom phase of its longstanding boom and bust cycle out here in the American west. Humans have been migrating from cities to fields and back again for a very, very long time, depending on fashion and the economy. Long skirts and head scarves are now in vogue for some women. Beards, axes, and homebrew are once again popular for some men. People are once more believing that a shack (now equipped solar panels) will set their children free, just like back in the seventies, and long ago before that.

But, my grandfather built that sod-roofed shack, turned it into a house, added a bunkhouse, and after thirty years of dry land farming through the Great Depression figured it made more sense to move to town than struggle to bring another crop. Most hippie communes collapsed, too. Farming is a very hard business. Farming is real work. Coding and zoom calls over wifi are not. Yet, tech money can buy a “homestead” where it desires. Or, again, a facsimile thereof.

My dad liked to make up words. He might have thought of his family’s move off the farm and into Billings as “townsteading.” When you sell the farm and move to town you still end up on a chunk of land with a house on top. But, this house is surrounded by a street grid lined with homes from which customers can be drawn, instead of farm fields and a dream of healthy grains.

Dad was funny but also quite practical. Moving to town has advantages. Collectively cultivated food can be bought at the store. Social opportunities are just down the (paved) road. Someone might even be paid to shovel the road for you, and spread the cost of that snowplow widely across a tax base. There could be schools that meet objective quality standards. There could also be crime, though rural crime is far more common than bucolic thoughts of country life might imply. Meth and opioids are as big or bigger a problem in much of the country, per capita, as they are in any city.

Having lived in both, I would question any easy answers about whether city or country life are easier or more authentic. Humans can build an economy most anywhere, particularly since the internet. The deeper questions are whether we can stay human while we do so. Are we willing to be neighborly? Are we willing to welcome folks to our homestead, even if they make more culture than they make babies to add to our eight billion?

I'm actually a lot less fixated on coastal big city living than you might think. As a teen, I lived in northern New Mexico, and bonded with the landscape and nature there. It's just that, for me, for now, coastal big cities work well for a variety of reasons.

What I see as affecting the Rocky Mountain West is that change happens, regardless of whether or not people want it. The upshot of this is that what got you there won't necessarily keep you there.

In particular, the values of small-scale capitalism got much of the rural West to where it is (or in many areas was) are no longer capable of keeping the rural West there. Having as little regulation on individuals and businesses as possible produces one outcome when a place is off the radar and of little interest to those outside it, and quite another outcome once that same place becomes trendy to some of those in the teeming cities.

This is for the simple reason that there is more economic opportunity in the city, so city-dwellers tend to have more money, and if very lightly regulated markets (which operate on a one-dollar, one-vote principle) are how decisions are made, this means affluent newcomers will get to outvote long-term residents.

The intellectually honest response is self-reflection and willingness to question the long-held values that are now failing to produce the desired outcomes. But questioning long-held values can be inconvenient, while conspiracy theories that direct anger onto convenient scapegoats allow such inconvenience to be avoided.